Alumni interview: Danau Tanu (Class of 1993)

Tell us a bit about yourself, and what you’ve been up to since you graduated?

The quickest way to describe myself would be to say that I’m a “Third Culture Kid” (or an adult “TCK” if you want to be precise). I have a pretty typical TCK story - my dad is Indonesian and of Chinese descent, and my mum is Japanese. I was born in Canada but I grew up mostly in Indonesia where I attended international school. I also went to an Indonesian kindergarten and a Japanese primary public school! Then, in my last year of high school, I moved to Singapore and stayed with a Singaporean family while going to CIS.

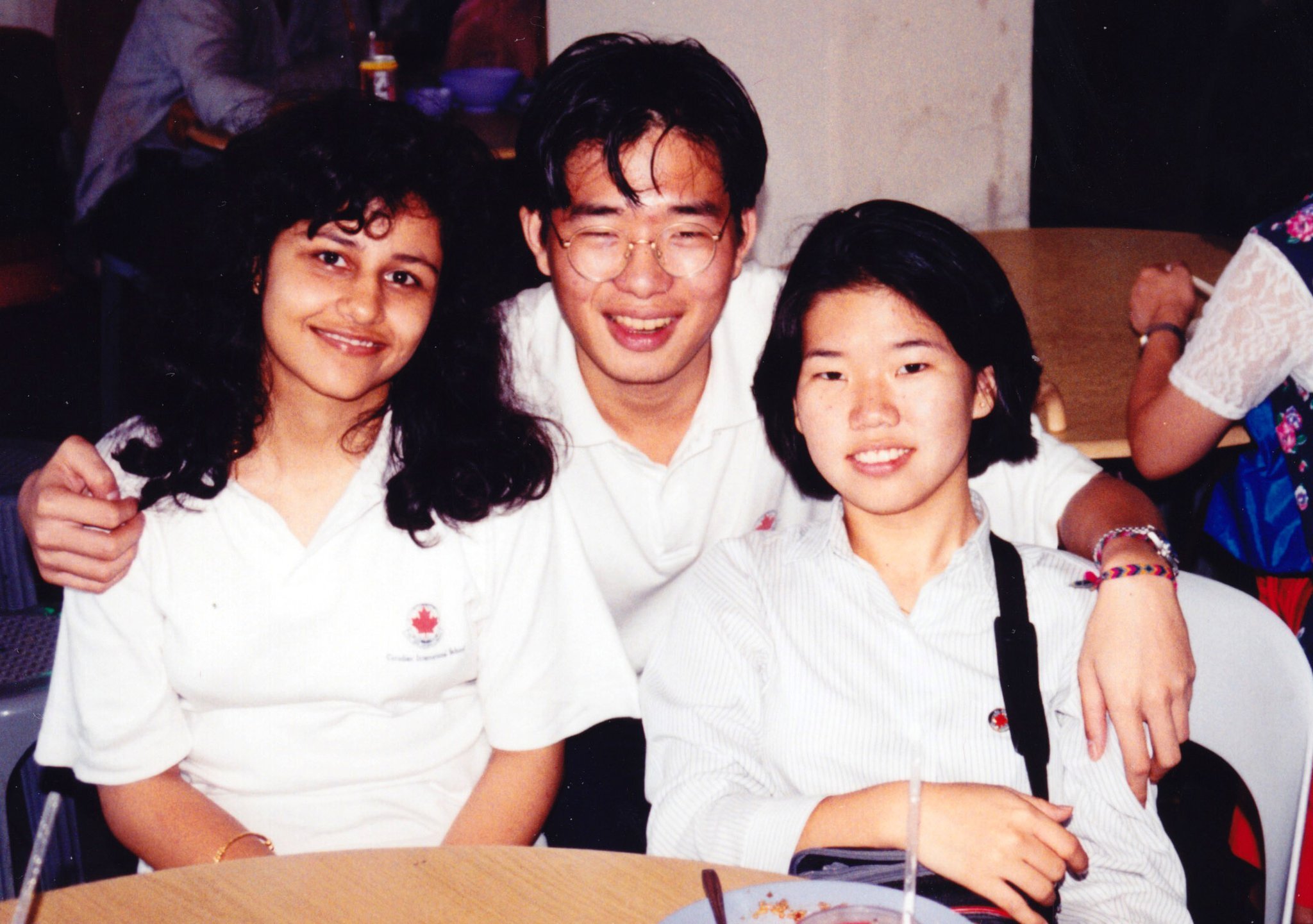

CIS had only been around for three years when I joined. And although I only studied there for one year, it had a huge impact on me! It was more than a school, it was a close-knit community and I am still in touch with my CIS friends. CIS also really changed my academic trajectory. When I first joined CIS, I was asked by the guidance counsellor about what I wanted to do after graduation. I remember being so sure that I wanted to study the sciences. But after one year at CIS, I completely changed course and told the same guidance counsellor that I wanted to study the arts, which got the counsellor a bit worried, I think!

In the end, I decided to go to the University of Toronto, and enrolled in an Arts degree. But after one year, I moved to Japan and studied Japanese literature instead… Until my family moved to Australia a year later, and I decided to join them. Thankfully, I was able to transfer some of my credits, and graduated in Australia with an Arts degree two and a half years later. I majored in Political Science and Asian Studies. It might sound strange that an Asian would take “Asian Studies” in Australia. But the thing is, despite being born to Asian parents and growing up in Asia, I knew close to nothing about Asian history. At both my international schools, the focus (back then) was always on European history.

After university, I was still not quite sure what I wanted to do. I had never really thought about my career, or “life after university”. For seven years, I did quite a few things. Then I decided to go back to university. I went to China to study the language for a bit, and then did a stint in Japan for a year doing postgraduate studies on a full scholarship. But I realised it wasn’t what I wanted. As I searched, I did some (brief) Christian mission work in Indonesia. At the end of this, my parents (who are what I call “serial migrants”) moved to Singapore. I joined them there while I was working for a Japanese company. After a year, my parents decided Singapore was not for them, so they moved briefly to Canada - where they decided it was too cold (laughs) before returning to Australia. Believe it or not, I followed them up until Australia (and kept switching jobs), after which my parents moved again to Indonesia. But this time I stayed in Australia.

It sounds crazy to make so many moves following your parents, but in hindsight I think I was trying to live “near home” after getting tired of living away from home when I was younger. It really can get complicated for TCKs who don’t have a geographical place or country to ground them and to call home. Your family is your home, so when they move, it’s like your “home” moves with them.

Anyway, in Australia, I worked as a freelance translator and taught Japanese and Indonesian at the University of Western Australia (jobs that I stumbled into). It was the first time I stayed in one place long enough to feel settled. It was a novelty for me to have the same friends living in the same city longer than two years, and I loved it!

It was during this time that I came across the term “Third Culture Kids” through a CIS friend, Anna. I caught up with her when I visited Indonesia, and out of the blue, she said, “Do you know that we’re ‘third culture kids’?” At the time, I had no idea what that was, or that this was even a thing, and didn’t think much of it. It wasn’t until a year later that I began looking into it.

I needed a research topic to do my doctorate but nothing felt right until a professor who was visiting our university asked, “Well, what makes you angry?” My gut reaction was, “The question ‘Where are you from’!” I’m sure CIS’ers can relate! It’s complicated, right? So, I bought the book, Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds by David Pollock and Dr. Ruth Van Reken and read it. I found my PhD topic—it felt right, finally.

Then, as I searched for a supervisor, I stumbled upon anthropology. (That’s right, I keep stumbling into careers!) It was a perfect fit: As a third culture kid, you are constantly observing cultures and populations as you grow up. You mix with people who are different from you, you see how others behave and you try to mimic to fit in. This is practically what anthropology is about, except now I could get paid to do it!

Just by researching the topic, I knew I had found what I was meant to do. I read a lot, about migrations, identity, mixed families, grief. A lot of reading, but also a lot of crying. I realised I wasn’t the only one struggling with my own identity, and feeling guilty for making a big deal out of this when we are living very privileged lives. It was a very emotional PhD, and being able to relate to it was therapeutic.

The “niche” of my doctoral research was about international schools. There was no real study about the experience of international schools for students from non-English-speaking backgrounds, which is different from the experience of, say, North American students. Many feel inferior because we might not speak English as well as some of the other kids. When I was young, I had a hard time understanding why the school culture was different from my home culture. There was this feeling that being Asian wasn’t as good as being white. Some call it internalised racism, and it’s something that we learn from the very make up of society. And schools are a part of that, even though international schools are trying their best to fight it.

So, what do you do now?

I completed my PhD in 2015. I taught at my university for a little while, and then moved back to Indonesia to be closer to my family (again, yup). I missed them, but also, my mom was ill. She’s better now and I’m back in Australia, working as a freelance translator for an embassy, while publishing out of my research. I’ve turned my research into a book called, Growing Up in Transit: The Politics of Belonging at an International School. Next, I am planning to focus on TCKs who are of mixed-heritage. I might consider going to Japan for that, actually.

The most exciting thing at the moment though, is the online public forum that some of us adult TCKs have started. I met a bunch of Asian TCKs in Bangkok earlier this year at the Families in Global Transition Conference. It’s a conference that began at Dr. Van Reken’s kitchen table 20-odd years ago. Ruth has actually visited CIS back in 2010 to give talks to students and parents, and that’s where I first met her. As for the conference, it’s for all TCKs and expats, as well as anyone working with TCKs. It’s an interesting conference, especially for TCKs. Many of us who grew up moving around and now work with TCKs usually attend the conference with our “work-mode cap” on with the intention to network and so on. But once there, we often unexpectedly find ourselves rather emotional at one session or another because someone is saying something that we can relate to but had never thought about.

So, I met other TCKs at the conference this year, and we clicked really well – we couldn’t stop talking to each other for the three days that we were there! Soon, about ten of us decided to launch the “TCKs of Asia – Online Public Forum” where we discuss issues relevant to those who attend international schools or move around a lot while growing up. Isabelle Min, who is a Korean TCK and is a transition coach, was instrumental in getting this going. So, we hosted our first forum in August of this year on the topic of “Hidden Losses of Third Culture Kids: Stories from Asia” with Dr. Van Reken as a guest speaker. We received very positive feedback.

You see, getting to see the world or attend international schools while growing up is an incredible privilege and we are fully aware of this. But if you are having to say goodbye to friends all the time because you move or they move, or if you’ve become culturally mixed and feel that nobody really understands you, then this can be hard. Many TCKs tend to bury this feeling to avoid being told they sound like a privileged brat, and try to just get on with life.

So, we’re trying to create a “safe space” that we wish we had 10 to 30 years ago when we were going through our twenties wondering why it was so hard to fit in, for example after we “repatriated”— for those of us who have places to repatriate to anyway! The TCKs of Asia online forum is still at an experimental stage, but if all goes well, we are hoping to replicate the forum in other languages too in the future, since not all TCKs speak English.

What is your biggest achievement since you have left CIS?

I would say publishing the book. Doing research on TCKs has had such a huge impact on myself. It helped me get over internalised racism, and so I hope the book will be helpful for others too. As far as I know, Growing Up in Transit is now being used in university courses in Japan and the US. For my next project, I’d like to write something even more accessible to everyone. Maybe something about mixed-heritage kids.

What are some of your best memories at CIS?

My research would not have happened without CIS. I remember fondly some of my teachers: starting up a dance club with Ms Tang and joking with Mr Field and the lovely Mrs Field, to name a few. And Mr Butler and Mrs Venhola deserve special mention: they had an especially strong impact on me. They were passionate about their jobs and ran their classes like a university course and my English skills never improved so much as it did in the one year I spent at CIS! Mr Butler gave me the confidence to write and Mrs Venhola showed us how fascinating the social sciences could be.

To show how much we appreciated Mr Butler, I remember getting my classmates to stand up on our desks while shouting, “O Captain! My captain!” like they did in the film Dead Poets Society starring Robin Williams and Ethan Hawke. The film was a favorite classic of English teachers, so I assumed Mr Butler had seen it too. I was wrong! He looked at us – a room full of teenagers in uniform standing on our desks – in shock! His jaw had dropped halfway to the ground and he looked confused. But he also seemed quite pleased, I think. He had no idea what we were doing, but he understood that we did it because we loved him and promised to watch the film afterwards, which he did (he told me years later when I caught up with him)!

Would you have any advice for students who have moved overseas for the first time?

I highly recommend for students and parents alike to read the book, Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds (3rd edition). Apart from that, I’m probably better at talking about how to leave a place than how to arrive. I would say children need to get the chance to say goodbye to friends and family. Don’t dismiss it by telling them they’ll make new friends anyway. Of course, it’s great that they’ll make new friends, but it doesn’t change the fact that their other friends will be on the other side of the globe or Instagram or whatever app is trending these days. As Naomi Horoiwa (1987) pointed out, for children, “going abroad is like a natural disaster: It comes when it comes, you have little control over it; and yet you have to deal with the consequences.” This can feel disempowering. To parents, I would say, if you can, try to involve your child in the decision-making process. And if that’s not possible, there’s still no need to feel guilty about it. As Ruth said in an interview with Sundae Bean, who runs a popular podcast for expats, first acknowledge and validate the child’s feelings if they do express a sense of loss before encouraging them about what awaits.

Another point I’d like to make is about the international school. Parents are often unaware that their child, who may not come from an English-speaking background, don’t just learn English and math at schools like CIS. They learn the whole culture of the school. No matter how hard parents try to prevent it, your kids may grow up to be culturally somewhat different from you. So, it’s good to be aware of this, otherwise you might be in for a surprise when they grow up!

The most important thing to remember is that kids know that it’s a great privilege to be able to see the world at such a young age or go to schools like CIS. And most do not regret their global childhoods in anyway, but it doesn't mean that they don’t pay a price for it. What we can do is support them in their journey by validating their feelings and experiences, and preparing them for what comes next.